Belonging: 2 Months at Site

|

| Is it really my blog if there isn't a picture of a beach in every post? |

|

| Meet Charlie: the sweetest angel kitten that is a great sport about enduring hours on a packed chapa. |

|

| A beautiful sunset captured while walking home from the market. |

It has been two months since I arrived here in my little town in southern Mozambique, marking 5 months total in this beautiful country. During these two months of what many of my Peace Corps education peers refer to as "boring time" before the school year starts, I've had plenty of time to reflect, refresh, and prepare for the journey that lies ahead.

I want to be transparent by saying that there is a very, very, sappy post ahead. Read at your own willingness to witness my vulnerable "realness."

About a month ago, I started reading a book titled Barking to the Choir: the Power of Radical Kinship by Gregory Boyle. I stumbled upon the book title and thought it was right up my ally--something that would remind me that I'm not the only one that spends so much time feeling everything.

The book is a collection of stories and experiences of Gregory Boyle, a Jesuit priest, who works with people involved in gangs in Los Angeles at his organization Homeboy Industries. I am not Catholic nor do I identify as a Christian, per-se, but I owe much of what I know about love and belonging to people who do identify this way including many Catholic nuns (Daughters of Charity, specifically) and people of faith that I met during my time as a student at DePaul University.

As I was reading Gregory Boyle's words, I frequently found myself choking back unexpected tears. He told stories of unconditional kindness, redemption, forgiveness, and the universiality of our shared humanity. He reminded me again and again with each little blurb that regardless of faith tradition--or lack thereof--there is something that connects us all. It's our need for belonging.

So, what does this have to do with me checking in after two months of near radio silence on my blog? Not a whole lot, actually, because I'm not going to write today about anything specific that has "happened" during this slow time. What I will write about, however, is a mini breakthrough that this book led me to.

When I came here to Mozambique, I was unsure if I would ever feel like I belonged. I've written before about sometimes feeling like I'm in a fishbowl, constantly being watched and observed even when doing the most mundane tasks. I felt like this discomfort was something I was just going to have to accept and perhaps ignore--that it would always be ever-present in my everyday reality as a foreigner living in a new place. There's nothing like being stared at through your fence by a band of children while you brush your teeth in the back yard to make you feel like you don't exactly "belong."

What I have been missing, however, is the insignificance of this feeling in the grand scheme of how incredibly amazing it is to have the opportunity to come face-to-face with how absolutely wrong I've been about the differences we share with one another across lines of country, culture, race, religion, etcetera. For some reason, I have (perhaps subconsciously) previously told myself that I could never understand what it was like to be x, y, or z person because I have never stood in their shoes or lived in their reality. The truth is, belonging really has nothing to do with how much you do or don't have in common with others. It isn't about blending in or standing out.

Maybe it is true that I will not ever fully understand what it means to be a Mozambican, but what I'm starting to realize is that there are many things about who we are as people that make the impossible seem possible. There will always be a few simple truths that blur the lines of difference and give us these "ah-hah" moments of what Gregory Boyle calls kinship.

"You like eating bananas for breakfast? Oh hey, me too!"

"Wait, your brother teases you all the time? Girl, I've been there."

"...someone you love is sick and you're not sure if they will ever get better? I carry that pain, too."

*sits under the mango tree in complete silence for hours while shelling peanuts, enjoying the shade and slight breeze together*

Kinship: the undeniable truth that we belong to each other.

We belong to each other. Let it sink in.

I belong to my mother who loves me so much that I cannot even fathom how she can forgive me for my teenage years (that aren't that distant of a memory). I belong to my mentors and teachers during college whom gave me one of the greatest pieces of wisdom I've ever heard, a Rumi quotation that says we must let our hearts break until they break open. I belong to the women who sell vegetables in the market here, who have given up afternoons to help me learn Xitswa, patient and humble in their teachings. I belong to my Peace Corps friends whose solidarity with my own mess-ups and confusion goes oftentimes unsaid in silent understanding that we are truly all in this together.

And all of these people belong to me. Near or far, they are here in my heart, strung together as a support network, a feeling of home, a bundle of lessons I've learned and loving kindness I've received. The kiddos I was so lucky to work with in East Garfield Park for four years? They belong to me in a bigger way than I could probably ever explain in words. They are me and I am them. Parts of their curiosity and eagerness stay with me as reminders that there is truly nothing more humbling than looking into the eyes of someone you perceived as different than you to only see yourself.

The people here in Mozambique are absolutely no exception to that. I am thousands of miles away from home, living in a place so visibly different from where I grew up and feeling like I belong here more than I ever thought I would. It's not about it being a different place, though. It's about seeing my life differently--that it doesn't just belong to me and me only.

If you read my blog, you may remember that a while back I wrote about hospitality in Mozambique and how amazed I was (and still am) at how generous and kind Mozambicans are to their guests. What inspired me to write this post was not only this great book I just read, but also how this hospitality has extended to kinship with such little time here. My host family especially consistantly opens their arms to me in kinship--they make me feel like I'm part of their family like flesh and blood. I don't know why, they just do. They don't question me and they don't hassle me about the things I can't do or the words I don't say right. Sure, they poke fun at me from time to time, but it feels no different than the way my own family in the states does.

|

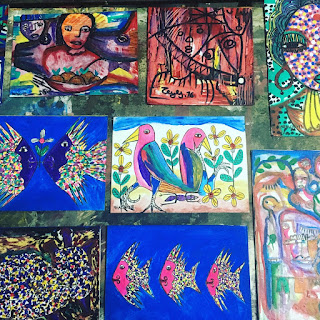

| Another afternoon spent with our host siblings coloring and stirring up chaos at our house. |

So what does family mean, in this case? Right now it feels to me like belonging, like kinship, like slow time spent sometimes doing nothing in particular without feeling uncomfortable in the silence.

I'm going to be a teacher here real soon. That means that I'm going to have a whole lot more people to "belong" to that will be counting on me to teach them what I know and for me to be equally as eager to learn about what they know, too.

How's that for kinship, Gregory Boyle?

With love,

Emily

My views and opinions are my own and do not reflect those of the United States government or Peace Corps organization.

Comments

Post a Comment